"Strategy is a commodity, execution is an art." Peter F. Drucker

Rebuilding Pacific Palisades: Historical Land-Use Patterns and Current Challenges

Introduction

The recent fires in Pacific Palisades have created an urgent need for rebuilding in one of Los Angeles' most affluent neighborhoods. This rebuilding process does not occur in a vacuum but within a complex regulatory environment shaped by decades of political struggle over land use in Los Angeles.

As Stephen J. Kaufman, founder of Kaufman Legal Group, observed in a recent LA Times roundtable on rebuilding Los Angeles: "Those of us who live in the hillside communities of L.A. enjoy the illusion of living in the wilderness... But the recent wildfires have us thinking: What if we're next?"

The fires have forced a reconsideration of development patterns in these vulnerable areas, raising fundamental questions about land use that echo throughout Los Angeles' regulatory history.

Andrew Whittemore's research paper, "The Influence of Private Interests in the Institutional Evolution of Los Angeles Zoning Administration," provides a critical historical context for understanding today's challenges.

By examining how different interest groups have dominated land-use politics through four distinct "regimes" since the 1920s, we can better understand the forces that will shape Pacific Palisades' reconstruction.

The Four Land-Use Regimes of Los Angeles

1. Era of the Speculator (1921-mid 1930s)

In the first era of Los Angeles zoning, small-scale land speculators dominated the political landscape. Despite planners' desires to create orderly communities with single-family homes on quiet interior streets and commercial activities clustered at major intersections, speculative interests successfully pushed for "over-zoning."

Commercial zoning was liberally applied to increase property values, with little concern for actual development potential.

Whittemore notes, "The City Council ended up zoning the city for commercial uses almost everywhere it may ever be desirable, and most major roads were given commercial frontage." By 1928, the ratio of commercially to residentially zoned land in Los Angeles was 25%, while the average in other cities was just 9%.

The speculative fervor resulted in "miles of vacant land along Los Angeles' boulevards throughout the 1920s and into the Depression." Homeowners had limited influence during this period, though some neighborhoods like Los Feliz began developing organizational skills to protect their interests.

2. Era of the Community Developer (mid-1930s-1960s)

The Federal Housing Administration's creation in 1934 marked a pivotal shift in land-use politics. FHA mortgage insurance policies strongly favored large developers building homogeneous single-family neighborhoods. Whittemore explains, "The FHA was very cautious in its definition of safe investment areas... a good score from the FHA depended on the containment of intensive uses and protection of low densities."

During this period, big developers and homeowners formed a powerful alliance against small speculators. The city began systematically down-zoning areas from multi-family to single-family designations. This era saw massive suburban expansion, with developments like Fritz Burns' FHA-funded Westchester project praised as "the largest and most spectacular feat of city building ever witnessed in Southern California."

This outward development pattern created the suburban footprint that defines much of Los Angeles today, including Pacific Palisades. However, it also established a pattern of exclusionary development and a large class of homeowners deeply invested in maintaining neighborhood character and property values through land-use control.

3. Era of the Homeowner (1960s-2000)

As available land for new development diminished in the 1960s, developers increasingly turned to infill projects in established neighborhoods. This shift sparked fierce resistance from homeowner associations, beginning what Whittemore calls "four decades of homeowner pre-eminence, an anti-growth machine."

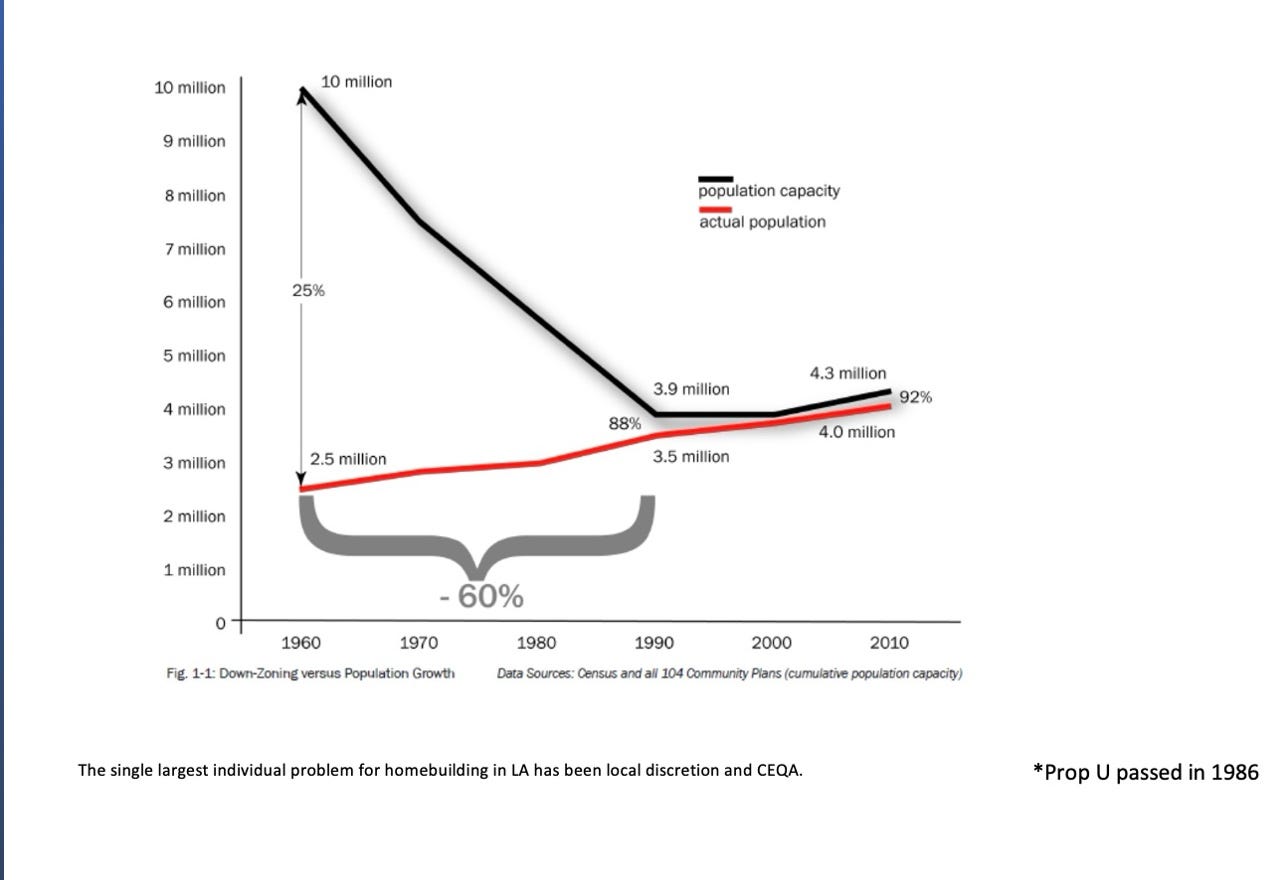

Homeowners successfully advocated for increasingly restrictive regulations: stricter height limits, expanded single-family zoning designations, increased parking requirements, and environmental reviews. Their political power culminated in 1986's Proposition U, which halved the allowable floor-area ratio in most commercial and manufacturing zones.

The anti-growth stance was often framed in moral terms rather than economic self-interest. As one homeowner activist stated, "Nobody is making a buck out of this homeowner association." This period saw the effective freezing of much of Los Angeles' development potential, with profound impacts on housing affordability and urban form.

Pacific Palisades epitomizes the neighborhoods that gained power during this era, with strong homeowner associations and a commitment to preserving low-density, single-family character despite regional housing needs.

4. Era of Balance (2000-present)

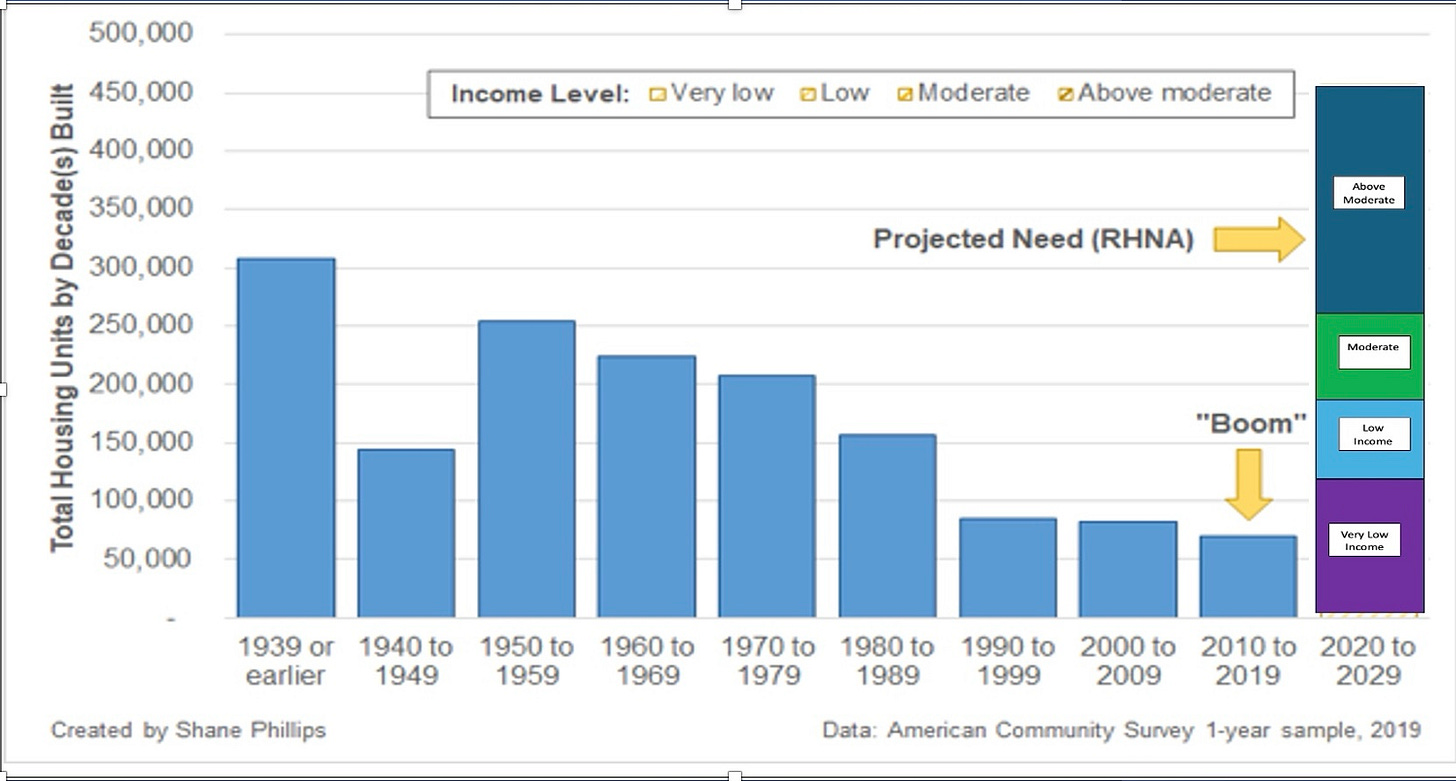

The last two decades have witnessed what Whittemore cautiously describes as a "diversification of Los Angeles' zoning policy." Faced with an acute housing crisis, city officials have introduced limited reforms to increase housing production, including adaptive reuse ordinances, residential accessory services, zoning, and transit-oriented development.

However, these changes have occurred against continued homeowner resistance without fundamentally altering the political dynamics established in the previous era. As Whittemore observes, despite the supposed room to grow, housing production has remained far below needed levels, with a persistent "bias in what gets permitted in Los Angeles."

Today's Pacific Palisades rebuilding debate occurs within this contested landscape, where housing advocates, climate concerns, and changing demographics increasingly challenge longstanding homeowner power.

Pacific Palisades Context

Pacific Palisades is a quintessential example of the powerful, wealthy neighborhoods that have historically shaped Los Angeles land-use politics. Developed primarily during the Community Developer era and politically ascendant during the Homeowner era, it embodies what Whittemore calls a "middle-class progressive regime" focused on quality-of-life concerns rather than growth.

The neighborhood's location in the wildland-urban interface makes it particularly vulnerable to wildfires. This vulnerability is exacerbated by the very low-density, car-dependent development patterns that its residents have fought to preserve. The strong home’s strong homeowner associations have consistently opposed densification, even as the region struggles with housing affordability and climate impacts.

The recent fires have created both a crisis and an opportunity how Pacific Palisades rebuilds will reveal whether the historical patterns identified by Whittemore continue to dominate or whether new concerns about climate resilience, housing equity, and sustainability can influence the process.

Current Rebuilding Challenges

1. Regulatory Constraints

The rebuilding of Pacific Palisades faces a complex regulatory environment created during decades of homeowner influence. Strict zoning codes limit density and height, while environmental review processes required under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) add layers of complexity and potential for litigation.

Recent developments have temporarily eased some of these constraints. As David Hitchcock of Buchalter notes in the LA Times roundtable: "Governor Newsom has temporarily suspended permitting and review requirements under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and the California Coastal Act, further easing regulatory barriers to reconstruction." However, this temporary relief doesn't address the fundamental regulatory challenges.

Dean Dennis of Hill Farrer points to deeper staffing issues: "The city, county, and legislature are talking about streamlining California's oppressive regulatory structure, which has been intentionally designed, over the years, to go slow and put up barriers. But what the city and county really need are bodies—people who are authorized to process and approve plans and permits on an accelerated basis."

The site plan review process established after the "Friends of Westwood" case in 1987 gives neighbors significant influence over development approvals, what Whittemore calls "institutionalized NIMBYism." Additionally, building code updates enacted since original construction may require substantial changes to rebuilt homes.

These regulations reflect the historical success of homeowner groups in creating what Whittemore describes as a system "basically of no growth or slow growth." While intended to preserve neighborhood character, these constraints may significantly complicate reconstruction efforts.

2. Community Pressure

Drawing on decades of effective political organization, Pacific Palisades homeowner associations will likely exert substantial influence over the rebuilding process. Based on historical patterns, these groups will likely advocate for:

"Like-for-like" rebuilding that maintains pre-fire neighborhood character

Minimal changes to density, height, or architectural styles

Resistance to any perceived densification, including accessory dwelling units (ADUs)

Strict environmental controls on rebuilding

As Whittemore notes, these groups often frame their concerns in terms of community character and environmental protection rather than property values, though economic interests remain central. Their influence with local elected officials has historically been substantial in affluent Westside neighborhoods.

3. Safety Requirements

Modern fire codes necessitate different building materials, construction techniques, and site planning than were common when much of Pacific Palisades was developed. Requirements for defensible space around structures may alter traditional lot configurations, while infrastructure upgrades for water systems and evacuation routes may require community-wide changes.

These safety imperatives potentially conflict with homeowners' desire to maintain historical neighborhood character, creating tension between individual property rights and collective safety. The rebuilding process must negotiate this fundamental tension.

4. Cost Considerations

Rebuilding faces significant financial challenges. Insurance policies may not cover the full cost of reconstruction to current building standards. Fire-resistant construction costs more than traditional methods, and supply chain issues continue to elevate building costs.

Even in wealthy Pacific Palisades, these cost pressures may influence rebuilding decisions and potentially open the door to policy interventions that balance affordability concerns with safety and environmental goals.

Applying Historical Lessons to Current Rebuilding

The historical patterns Whittemore identified offer insights into how the Pacific Palisades rebuilding process is likely to unfold if past patterns continue.

From the Era of Homeowner Control (1960s-2000), we can anticipate that neighborhood groups will dominate the conversation around rebuilding. Environmental concerns may be strategically deployed to limit development potential, and City Hall will face significant pressure from organized residents to maintain the status quo. As Whittemore observes, "Through the election of anti-growth candidates to the City Council, the suburban homeowners of the Valley and the Westside were able to impose their preferred model of growth, basically a system of no growth or slow growth, on the entire city."

However, elements from the emerging Era of Balance (2000-present) suggest countervailing pressures. The regional housing shortage creates competing public interests that may influence rebuilding policies. Implementing new construction technologies that. address safety and environmental concerns may be.

(Check out this Los Angeles housing entrepreneur building the world's first carbon-negative and sustainable ADU from wood waste, primarily sourced from California's forests. This approach avoids clearing land, which only exacerbates fire danger.)

Most significantly, the disaster may create political space for targeted regulatory relief for rebuilding—potentially including provisions for increased density or sustainability.

The fundamental tension identified in Whittemore's conclusion remains relevant: "The first decade of the twenty-first century may, at last, have been the decade in which planners and legislators, even though still driven by the concerns of an affluent minority, represent a diverse enough segment of the electorate to at least be trying to expand the definition of the public served by land-use regulation."

Key Questions for Rebuilding

Should rebuilt homes be required to meet current codes or maintain their original character?

The tension between preserving neighborhood character and implementing modern safety standards represents a central challenge in rebuilding Pacific Palisades. Historical precedent suggests homeowners will strongly advocate for character preservation, emphasizing the neighborhood's aesthetic and cultural aspects. However, safety considerations—particularly given the area's demonstrated wildfire vulnerability—demand adherence to current building standards.

Randall S. Leff notes in the LA Times roundtable that "new construction will incorporate advanced fire-resistant materials, underground utilities and modernized landscape design to mitigate future risks." However, David Hitchcock emphasizes the importance of reassuring homeowners "that while the rebuilding process is lengthy, there is no need to make rushed decisions under pressure... The permitting process must be streamlined, particularly for those seeking to rebuild their homes as they were."

This question reflects the broader tension that Whittemore identifies between homeowner interests and public safety. The outcome will reveal whether the "Era of Balance" has truly shifted political dynamics or whether homeowner interests continue predominating as they did in the previous era.

Can rebuilding incorporate climate resilience and sustainability?

The fires themselves demonstrate the climate vulnerability of current development patterns in Pacific Palisades. Rebuilding presents an opportunity to create a more fire-resistant and sustainable community through improved building materials, energy systems, water management, and vegetation practices.

In the LA Times roundtable that rebuilding efforts should prioritize modernization, such as "cost-effective water storage tanks that could serve dual purposes: emergency water reserves for hillside communities and 'hydroelectric batteries' when integrated with abundant solar energy." This represents the kind of innovative thinking that could make communities more resilient.

However, as Whittemore's analysis would suggest, such changes may face resistance if they conflict with established neighborhood character or add costs. The rebuilding process will test whether climate concerns have become sufficiently powerful to influence land-use decisions in ways that were impossible during the homeowner-dominated era.

How will the city balance streamlining reconstruction with proper oversight?

Disaster recovery typically creates pressure for expedited permitting and reduced regulatory barriers. However, Whittemore documents the historical development of Los Angeles' land-use regulation, showing how each regulatory layer was added in response to perceived abuses or community demands.

Dean Dennis emphasizes in the LA Times roundtable that speed is essential: "We can't do it all – or perfectly – but we can make progress in a relatively short timeframe with concerted effort.

The worst insult to injury is to lose everything you loved and then be doubly screwed by the time and money it takes to recover." He points to examples of successful rapid rebuilding: "Everyone points to the rapid rebuilding of the 10 freeway after the Northridge earthquake spearheaded by Mayor Riordan. Things can happen when someone takes charge."

The city must navigate between facilitating rapid rebuilding and maintaining appropriate oversight to ensure safety, equity, and environmental protection. The role of neighborhood councils, established during the "Era of Balance" and dominated by land-use concerns, will be particularly important in this balance.

Should rebuilding allow for additional housing units?

Perhaps the most contentious question is whether Pacific Palisades rebuilding should include provisions for increased housing density, particularly through accessory dwelling units (ADUs). Such units could address regional housing needs while maintaining the single-family character of the neighborhood.

In the LA Times roundtable, David Hitchcock advocated that "Los Angeles County, the city of Los Angeles, and the city of Pasadena should expedite permitting for modular and prefabricated housing, mirroring the streamlined process established for accessory dwelling units (ADUs)." This suggests that ADUs could be part of a broader strategy for efficient rebuilding.

Whittemore's analysis suggests this question directly confronts the core dynamic of Los Angeles land-use politics: the tension between homeowner interests in maintaining exclusionary patterns and broader regional needs for housing production. The outcome will indicate whether the "Era of Balance" has truly shifted power dynamics or created limited exceptions to homeowner dominance.

Stakeholder Analysis

Pacific Palisades Homeowners

Historically the dominant force in land-use decisions, homeowners affected by the fires face competing priorities. Their primary goal is rapid rebuilding with minimal changes to neighborhood character, maintaining the low-density, high-value environment they've invested in preserving. Yet they also face concerns about safety improvements and insurance coverage that may require modifications to traditional patterns.

Dan Shea, in the LA Times roundtable, notes that "rebuilding will be a long and complex process, with supply chain disruptions and labor shortages, among other things, slowing progress." He adds that "insurance companies will continue reassessing their exposure – leading to rising premiums or reduced coverage in high-risk zones." These pragmatic concerns may influence homeowners’ positions on rebuilding approaches.

Whittemore's analysis suggests these groups will be highly organized and politically effective, drawing on decades of experience influencing land-use decisions. Their tactics, refined during the "Era of the Homeowner," typically include mobilizing neighborhood associations, engaging with local elected officials, and challenging unwanted changes through environmental review processes.

City Planning Department

The Planning Department approaches rebuilding with institutional memory of the conflicts Whittemore documents. Their primary goal is safe, code-compliant rebuilding that meets current standards while respecting community character. Secondary concerns include housing production, environmental protection, and climate resilience.

David Hitchcock notes that the city of Pasadena has made some progress in this direction, now offering "virtual planning consultations for property owners affected by the fires, enabling them to meet with planning and zoning officials remotely, eliminating the need for in-person visits."

However, Dean Dennis argues more fundamental change is needed: "The city needs something like a hundred new people. There are private planning firms, retired planners, and trained personnel throughout this country. They should be brought in, paid for living expenses, paid good salaries, and empowered to make decisions and get things moving."

The department's approach reflects the tentative "Era of Balance" Whittemore identifies. It attempts to accommodate multiple interests while navigating the political influence of homeowner groups. The department's decisions will reveal whether institutional priorities have meaningfully shifted since the height of homeowner influence in the 1980s and 1990s.

Housing Advocates

Although historically less powerful in Pacific Palisades, housing advocates view rebuilding as an opportunity to increase the housing supply in an area that has largely resisted densification. They emphasize the potential for ADUs and gentle density increases to address regional housing needs while maintaining neighborhood character.

Stephen J. Kaufman emphasizes that "housing was already Los Angeles' most pressing issue before the fires.

The fires have exacerbated the affordable housing crisis. Displaced residents are straining an already tight market, increasing rental demand, and forcing many to look for alternative housing farther from their communities, jobs, schools, and support networks.

As Whittemore notes, housing advocacy has only recently begun to challenge homeowner dominance in Los Angeles land-use politics. The Pacific Palisades rebuilding process will test whether this emerging influence extends to affluent neighborhoods that have historically been most effective at resisting change.

Environmental Groups

Environmental perspectives on Pacific Palisades rebuilding are complex. Some groups emphasize the need for sustainable rebuilding that addresses wildfire risk through improved building standards and reduced carbon footprint. Others may align with homeowner interests in limiting density and preserving green space.

Stephen J. Kaufman notes in the LA Times roundtable that rebuilding presents an opportunity to "address the issue of climate change. Until we confront those issues, we must reconsider our lifestyle choices or live in fear of the next fire or mudslide. City planners and developers also may need to ask: Should we continue building in these vulnerable areas at all?"

This complexity reflects what Whittemore describes as the strategic deployment of environmental concerns by homeowner groups during the "Era of the Homeowner." The rebuilding process will reveal whether environmental advocacy has evolved toward a more comprehensive vision that addresses both local and regional sustainability concerns.

Potential Paths Forward

Status Quo Approach

The historically dominant approach would prioritize like-for-like rebuilding with minimal changes to neighborhood character, perhaps incorporating modest safety improvements required by current codes. This approach would maintain Pacific Palisades' existing development patterns while expediting recovery for affected homeowners.

As Dan Shea of Objective noted in the LA Times roundtable, many residents have "an overwhelming desire to recapture a feeling of normalcy." This impulse toward restoration rather than transformation is powerful, especially in affluent communities with strong homeowner influence.

Whittemore's analysis suggests this approach would reinforce the patterns established during the "Era of the Homeowner," maintaining exclusionary development while potentially increasing vulnerability to future fires. It represents the path of least political resistance given established power dynamics.

Moderate Reform

A balanced approach would combine expedited permitting with enhanced safety requirements and allowances for limited densification through ADUs or similar gentle density increases. This approach attempts to balance respect for community character with acknowledgment of regional housing needs and climate concerns.

Several experts in the LA Times roundtable endorsed this middle path. Randall S. Leff of Ervin Cohen & Jessup LLP suggested that "while wildfires pose significant challenges, they also present an opportunity to reimagine and expand housing within the existing landscape. By embracing innovative, forward-thinking solutions, we can develop more resilient and sustainable communities."

This path aligns with what Whittemore cautiously identifies as the emerging "Era of Balance," recognizing multiple stakeholder interests while preserving the fundamental character of single-family neighborhoods. It represents an incremental shift rather than a fundamental transformation of land-use politics.

Transformative Rebuilding

A more ambitious approach would use the rebuilding process as an opportunity for comprehensive redesign focused on fire resilience, environmental sustainability, and housing diversity. This could include significant density increases in appropriate areas, integration with regional housing and transportation planning, and innovative approaches to community design.

Stephen J. Kaufman frames this opportunity in the LA Times roundtable: "The effort to rebuild Los Angeles presents a vital opportunity for government and the private sector to work together to tackle systemic barriers, streamline processes and reassess outdated regulations that have long hindered the development of smart, affordable housing. It also presents an opportunity to rethink planning issues that may not have been apparent when these communities were developed decades ago."

While least likely given the historical patterns Whittemore documents, this approach would represent a genuine shift away from the homeowner-dominated era toward a more inclusive vision of land-use regulation that prioritizes regional needs alongside neighborhood character.

Recommendations

Create a Pacific Palisades Rebuilding Specific Plan

A specific plan would establish clear standards for rebuilding while streamlining the permitting process. This approach draws on Los Angeles' history of using specific plans to manage development in sensitive areas, providing certainty for homeowners while ensuring community-wide coordination.

David Hitchcock advocated for this approach in the LA Times roundtable, suggesting that "Los Angeles County, the city of Los Angeles and the city of Pasadena should expedite permitting for modular and prefabricated housing, mirroring the streamlined process established for accessory dwelling units (ADUs). By pre-approving certain architectural designs and modular structures, these jurisdictions could significantly reduce permitting and inspection timelines, accelerating reconstruction efforts."

The plan should balance preserving neighborhood character with necessary safety upgrades and modest provisions for increasing housing options. Community involvement in plan development is essential, but it should include diverse stakeholders beyond traditional homeowner associations.

Implement Tiered Approvals

To balance efficiency with oversight, a tiered approval system would:

Fast-track exact rebuilds that incorporate required safety upgrades

Provide moderate review for slight modifications that maintain the same building envelope

Require full review only for significant changes in size, height, or use

Dean Dennis emphasizes the urgency of this approach in the LA Times roundtable: "Everyone is very energized and eager right now to make things happen. But we have seen businesses firing off in all different directions in the hope some efforts will bear fruit. But to be successful, it is important to have a little patience and a plan, and, for a recovery of this immense scale, strong leaders."

This approach acknowledges the legitimacy of homeowners' desire for rapid rebuilding while maintaining appropriate oversight for changes affecting community character or safety.

Continue to streamline City Hall processes and empower its talent.

Continue to implement and execute better ideas.

Attract more private sector capital.

Incentivize Resilience

Rather than simply mandating changes, incentives can encourage improved rebuilding through:

Fee waivers for fire-hardening improvements beyond code requirements

Expedited processing for projects incorporating ADUs or other housing innovations

Tax benefits for sustainable rebuilding that reduces environmental impact

Stephen J. Kaufman notes in the LA Times roundtable that "requiring the use of more fire-resistant building materials in the construction process – particularly in hillside areas – should be a pre-requisite, but we must make these resources readily available to homeowners and ensure that this requirement does not slow down the rebuilding process."

This incentive-based approach represents an evolution from the rigid regulatory framework that Whittemore documents toward a more flexible system that acknowledges multiple goals.

Establish Community Design Standards

Coordinated design standards would create consistency while allowing individual expression through:

A palette of fire-resistant materials that maintain aesthetic compatibility

Landscape requirements that create defensible space while preserving visual character

Infrastructure improvements shared across properties to improve community resilience

Randall S. Leff suggests in the LA Times roundtable that "new construction will incorporate advanced fire-resistant materials, underground utilities and modernized landscape design to mitigate future risks." Such standards would address the legitimate concern for neighborhood character that has motivated homeowner activism while ensuring safety and sustainability.

Conclusion

The rebuilding of Pacific Palisades after the recent fires exemplifies the ongoing tensions in Los Angeles' land-use politics that Whittemore documents. The historical patterns of speculator dominance, community developer influence, homeowner control, and tentative balance continue to shape today's challenges.

The LA Times roundtable highlights both the challenges and opportunities of this moment. As Jay Hawkins of PNC Bank observes, "Wealth disparities and insurance availability can play a large role in post-disaster economies. Wealthier residents and businesses often rebuild more quickly, while lower-income residents may take insurance payouts or cash buyouts and move elsewhere." This dynamic threatens to reinforce the patterns of exclusion that Whittemore documents throughout Los Angeles' land-use history.

However, Stephen J. Kaufman sees an opportunity: "Los Angeles has long been a symbol of bureaucratic inefficiency in residential and commercial development. The wildfire recovery effort presents us with an opportunity to reassess outdated laws and streamline regulations to balance legitimate environmental, growth, and safety concerns with practical solutions for developing sustainable communities."

The process offers an opportunity to move beyond the strict homeowner dominance of previous decades and toward a more balanced approach that acknowledges the legitimate interests of all stakeholders. Success requires understanding how historical power dynamics continue to influence current debates while recognizing emerging priorities around housing affordability, climate resilience, and environmental sustainability.

If handled thoughtfully, Pacific Palisades' rebuilding could become a model for other communities facing climate-related reconstruction challenges. It would demonstrate how Los Angeles' complex land-use history can inform a more inclusive and resilient future. As Whittemore concludes, this represents an opportunity to expand "the definition of the public served by land-use regulation" beyond the "affluent minority" that has historically dominated.